This post is a design commentary about a game I wrote. The game itself is short (shorter than this post) so to encourage folks to read along with the commentary, I'm also making it free for the next week. Please go download a copy and follow along!

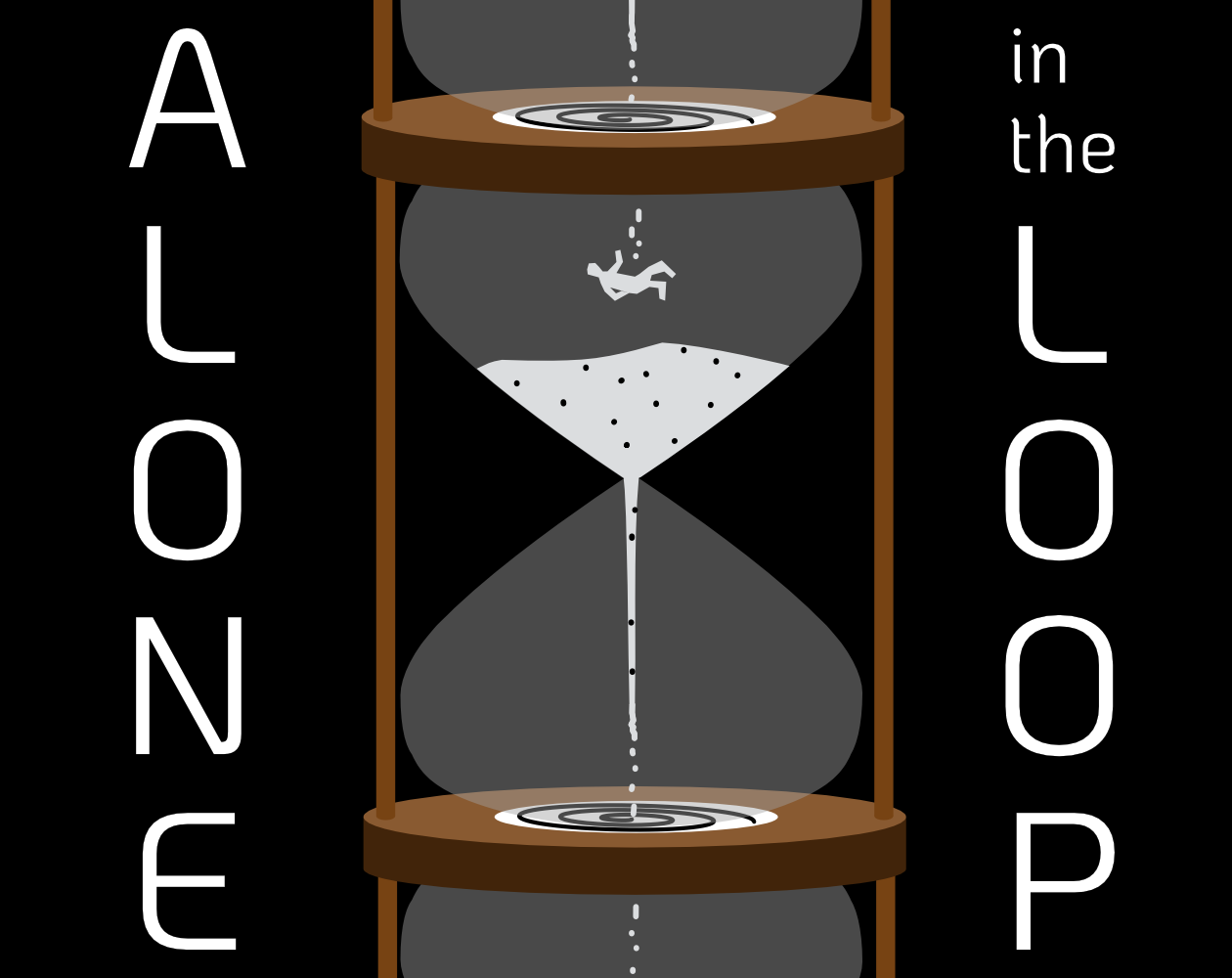

At the beginning of the year, I published Alone in the Loop on itch.io. It’s a solo journaling RPG that hacks Takuma Okada’s incredible Alone Among the Stars to tell a story about a lonesome time traveler trying to shift the tides of fate. It pivots on themes of isolation, despair, and hope in the face of a trial that must be undertaken alone. The time traveler may, if they’re lucky, be able to convince someone of the truth of their situation, but with each new loop, all that effort will be unravelled once again. They may, if they’re lucky, meet another time traveler, but that other traveler may be aloof and mysterious, wrapped up in some grim mission of their own.

Whether by choice or by circumstance, the time traveler must avert a disaster or shift the timeline in some particular way before they can return to linear time. And even if they succeed, they’ll leave the experience profoundly changed by it.

I have a deep fondness for the lonely time traveler trope. I love the grandiose tragedy of the traveler’s descent into despair in the face of failure after failure, all underpinned by an enduring hope that somehow, some way, the world can be changed for the better. It’s existentially brutal and beautifully idealistic all at once, and its all heightened by the way that its stakes play out only in the mind of the singular protagonist. I badly wanted to make a game about it, and what better format than a solo journaling game.

The System

To do this, I hacked Alone Among the Stars, a brilliantly simple engine driven by a single die and a deck of cards. Play alternates between dice rolls and card draws, with players describing what their character finds on a journey through space. Each card represents a unique discovery, divined by combining the suit (a category: people, flora, structures, etc.) and the rank (a bit of imagery or context: rivers, canyons, oceans, etc.). The game is so short, smart, and freely available that you should read it — or even play it — right now if you’re not familiar (and pay the suggested price if you can). It’s a powerful and adaptable system, an elegant combination of context (Alone) and place (Among the Stars).

In adapting it for Alone in the Loop, I chose to focalize loneliness rather than peaceful solitude. To transpose it into a plot contrivance instead of an aesthetic space, I made three of the suit categories focus on the metaphysics of the time loop while most of the card ranks describe the events and people encountered during the loop. Player characters’ interactions, even ones with other people, are contextualized by what can be learned about the loop itself. These people and events are only ephemeral details to be washed away when the loop resets, until the time is right to end it.

To reinforce this loneliness, the fourth suit (Clubs) is all about contending with the isolation of the loop. It might involve your character lashing out, breaking down, or otherwise faltering in their resolve. It plays up the tragedy of being unable to meaningfully seek help, unable to relate your struggle to another person. It’s heavy, but it strikes the right note for this kind of story.

"Establish the Loop"

Alone Among the Stars is a toolset for wandering around within an aesthetic palette, with suits and ranks characterizing the surroundings. It treats beginnings and endings loosely, inviting players to linger on individual moments along their journey. But Alone in the Loop centers on a plot conceit rather than an aesthetic identity. To help with up-front ideation, I introduced a setup phase before ongoing play begins. Players use the suits of drawn cards to determine the details or choose freely from the options.

First, players establish the nature of their time travel capability, which roots their story within genre. Time travel powered by invoking a deity suggests a mythic setting, while time travel driven by a high-tech device suggests something more science fictional. Lines will certainly blur, but it’s helpful to start somewhere. Each option also asks a brief question (How do they contact the deity? Who built the high-tech device?) to get the player thinking about the details of their loop.

Second, players establish a reason for repeating the loop. This provides personal stakes for the story; a time traveler who’s trapped in the loop will pursue different ends than one who repeatedly chooses to go back so they can save someone from a tragic fate.

Finally, we establish the length of the loop. The range is wide, using suits and ranks to define a period of time between 5 minutes and 13 weeks. Since this choice dramatically effects the scale of storytelling, I have players draw three cards and choose their favorite option. The time increment (minutes, hours, days, or weeks) will also determine the number of key events (Inflection Points) that occur in each iteration, borrowed from how Alone Among the Stars uses a die roll to determine how many discoveries will be on each new planet.

Once these details are established, the player begins journaling their experience of the loop, starting after the first instance of turning back time. By skipping over the inciting incidents of the loop, they leave narrative gaps to fill as the story unfolds. They also skip straight past the novelty of the time loop, to a moment where the time traveler’s resolve might start to waver.

"Live the Loop"

During the story, players draw a set number of cards for each time they go through the loop; that number represents the amount of Inflection Points they’ll encounter, important events or details that shed light on the nature of the time loop.

But stories about time loops often play with pace and timing. They swing big and lean into themes of trauma, memory, and causality. Because the clock will roll back, they deploy things like shocking death, sudden violence, cruel words, and queasy foreshadowing. The imprint of the events upon the mind of the time traveler are all that will remain, so they can become heightened and stark, akin to nightmares.

To this end, Alone in the Loop has two special affordances for shifting pace. The first is simple: when it makes sense, restart the loop early. If your character reaches a dead end, encounters an impending tragedy before it’s due, or even finds themselves mortally wounded, the loop can be cut short to shift the pace and escalate the dramatic momentum. At any time, things can go horribly wrong in new ways, making the loop feel volatile, dynamic, and malleable. Despite the trauma of premature tragedy, it’s also a source of hope: it’s proof that there are avenues yet unexplored, changes so dramatic that they can derail the story entirely. That breadth of possibility means that what the traveler seeks is still attainable.

The second affordance allows players to montage a number of iterations together. The set of cards they draw for each iteration (for example, 4 cards for a loop measured in days) can be repurposed to allow each card to represent one crucial event in the entire iteration. As the stakes escalate and the hero becomes more desperate to change their fate, one way to articulate their despair is to accelerate the pace of the story and depict failure after failure in quick succession, culminating in a breaking point that helps them find a new approach. The montage rule is directly inspired by the media that inspired this game, and provides a way to mechanize that story beat.

"End the Loop"

Ending the loop is a tricky storytelling maneuver. It’s most successful if there’s just enough setup to show it’s possible, but lingering suspense around the execution of the plan. After all, if it works, the final loop is permanent; anything that happened, any sacrifices made, can’t be undone without undoing the work of resolving the loop’s key problem. To wrestle with that drama, I instruct players to decide at the beginning of an iteration whether or not it’s going to be the final one. This way, there’s still an uncertainty about how to actually accomplish the conclusion they have in mind with the story beats they get along the way.

Since there’s always a possibility that the final iteration goes awry in some way, the game presents four possible endings. As before, you can either draw or choose freely. The choice to include several endings was important to me because it helps to visit some of the themes one last time. One ending is failure; tragedy unprevented or an existence trapped in the loop. Another is a restoration, a single choice or compromise that realigns the world and sets things right, leaving room for its own sort of sadness depending on what the player chooses to give up. The others involve finding a solution, but they emphasize different ways that the player character has been changed by the ordeal.

Even after everything has been resolved and the world is allowed to move on, the time traveler remembers it all. There’s a rich, existential sadness that they must be left with, bearing the weight of remembered traumas that were ultimately undone, but were entirely real when they happened. Perhaps those events still reverberate through some alternate timeline. To reach the end of the time loop is triumphant, but also bittersweet.

If I Could Go Back…

I’ll likely revise this game at some point. I can already see little things I might change: some wording is too terse, I’d like to more strongly justify why I invite players to choose options directly instead of drawing cards during certain steps, and I could do more to make the rank descriptions more evocative and enticing; right now some are utilitarian or bland.

I could also realign the suits for the endings; the most tragic ending should align with Clubs, the suit that contends with despair and isolation. This would also make the safety advice at the beginning (which suggests removing the clubs cards before playing through the loop in order to avoid the darker emotional themes) more effective in the ending phase.

Conclusion

Alone Among the Stars is fundamentally about a sense of place, about an observational experience while alone in nature. Adapting it involved some relatively heavy scaffolding to repurpose its system towards inhabiting a plot trope instead, but I feel that the adjustments pull their weight, and I’m proud of the game on the whole.

This post ran quite long, even after revising, but it was great fun to write! A lot of tiny, invisible choices go into game design. Articulating it in detail helps me bubble up some of the subconscious choices and re-evaluate what I works best. Some of my thoughts here might even be worth distilling into play advice and other revisions if I choose to revisit this project at some point. Either way, the exercise was fun and I highly recommend it to other designers; tell me about your work!