Over the holidays, I typically try to start a bunch of games from my backlog. With my time inevitably broken up around relaxing with family, I rarely get very far into any of them. Games with a large scope, whether that’s with design or with narrative, usually fall by the wayside before they can make strong impressions. So when I booted up Dread Delusion on my steam deck, I wasn’t expecting to be drawn in quickly enough to stick with it while I visited family.

Well, I was wrong. It became a minor obsession for a couple of weeks. I became enamored of its weird fantasy-horror setting and its grim history, I was repeatedly charmed by its great deal of sharp characters and thoughtful writing. But beyond that, it made me think a lot about choices in video games and the way players interact with them.

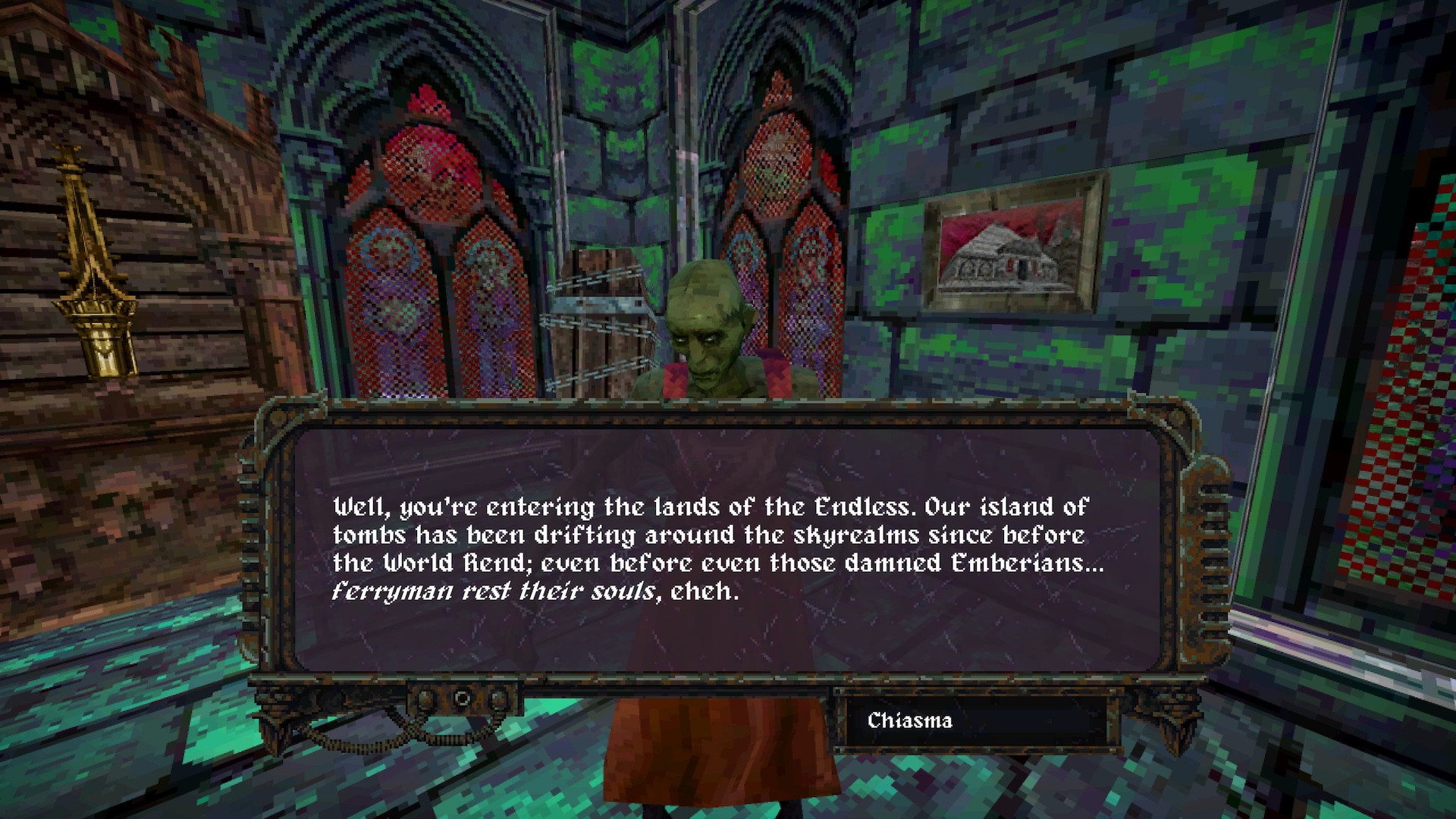

Dread Delusion is an indie take on an Elder Scrolls-style first-person CRPG. It takes place in a post-apocalyptic open world split across sparse, floating islands in the wake of a great cataclysm called the World Rend that brought the surface below to ruin. You begin the story as (tell me if you’ve heard this one) a prisoner, captured and jailed by inquisition agents rooting out unlicensed magic use and deity worship. You’re quickly ushered from your cell and forced to join the inquisitors’ ranks as they throw bodies at the fortress of renowned pirate Vela Callose, who has evaded their pursuit thus far. Bring her to justice, you are told, and you’ll earn your freedom.

From the start, the Apostatic Union and the inquisitors they employ can hardly be regarded as actual allies. As you’re go from prisoner to indentured inquisitor, you’ll follow the pirate’s trail and recruit her old crewmates to help you track her down. Along the way, you’ll see more of the inquisitors and the world that their God Wars have brought about. To the Union’s initial credit, you’ll find that communities across the isles have been liberated from pagan deities that demanded brutal sacrifices in exchange for prosperous farmlands and fortunate weather. But you’ll also find that in the absence of these hungry gods, the promised prosperity has vanished as well; crops struggle, Union-regulated trade squeezes folks dry, and many wonder if they’ve been freed from a tyrannical divinity only to be subjugated by imperialist bureaucracy.

Throughout the game, you’ll meet struggling folk and seek to find solutions to their problems that don’t leave them in even worse situations. Across each of the three regions in the world, you’ll find evidence of the historical clashes between the god-worshipping Wikkans (yes, that’s really what they’re called) and the Apostatic Union—”apostatic” as in “apostates”, because they’ve systematically rejected their gods. You’ll meet the Endless, zombie folk who have unlocked eternal life but have suffered immensely under its weight, and the denizens of the Clockwork Kingdom, who erected an inscrutable machine god to rule over them in place of the old ones (take a guess at how that’s going). All over these isles, folks are having a pretty bad time, and many of them wonder whether the new order should be dismantled, if the old ones should be restored, or if an entirely new vision is the only way forward. Each kingdom entangles you in a major decision that will affect its peoples’ future for decades to come. And as the central plot returns to Vela and her own world-changing ambitions, all things culminate in a final choice, with the fate of everything in the balance.

Despite the dour state of the world and its focal regions, Dread Delusion is more often interested in existentialism, tragedy, and hope than it is in true despair. Beneath its fleshy, low-poly surface is a profound sense of place and people. The folks whose stories you’ll help shape are always present to argue their case, lend their life experience, and give each choice weight. And no matter how wrong every answer feels, no matter how poorly an outcome might go, the writing is never smug about this in the way that something like The Outer Worlds wallows in the frustrating imperfection of binary choices. Dread Delusion is content to present you with a problem and let you solve it as best you can, within the limits of what you understand and can accomplish; sometimes that isn’t as much as you might hope.

Steam has a user-applied tag called “Choices Matter” that represents a particular ideology of player expectations. To suggest that “choices matter” means that decisions made by players must be rewarded by meaningful changes to the story and systems of the game. Steam’s users have have not applied this tag to Dread Delusion (nor The Elder Scrolls titles that it draws heavily from), but they have applied it to works in a similar vein like Avowed and Tainted Grail: Fall of Avalon, which I find fascinating. The writing in Dread Delusion seems determined to bear the weight of choice, insisting that you have the power to change the world’s fate with your decisions…but the visuals and systems of the game have limited tools to surface these changes in the world. Few choices have immediate material outcomes in the world (though many change how various factions regard the player). However, Dread Delusion’s procedurally-built ending incorporates each key quest line’s resolution, resulting in a closing narration that’s very clearly shaped by player decisions.

On some level, Dread Delusion seems conflicted about whether or not its choices matter. Unlike other games in this style, it leaves space for players to avoid choices entirely. Most of these decisions don’t truly have to be made, by and large; completing the primary quest of the game does not depend upon resolving the major plot lines of each region. No, you can wander around until you find and recruit the mysterious strangers key to your central mission and leave each kingdom to contend with its fate however it might. Sometimes, that feels like it’s the thing you ought to do. But the threads of fate pull, even gently, and there’s always the promise of a “glimmer of Delusion”, the game’s advancement currency, at the end of these major decisions.

The only other way to acquire glimmers of Delusion is the collectibles scattered throughout the isles. Notably, killing monsters or amassing resources does not provide Delusions. Thus, players are encouraged primarily to explore the world and resolve the stories within it. There’s no way to reverse decisions by loading saves; the game asks you to decide what your character believes and express it through choices that are presented to them, committing to the outcomes and making the story of the isles feel like something they molded. It feels often like it leans into the popular tendency of players to voraciously move quests from the “Active” to “Completed” columns of the journal. Quests unfinished would feel like books left half-read, movies half-watched. A story should have an ending, even if the world around it has to live with the enduring consequences.

An often-referenced video game design concept is the illusion of choice, in which players’ actions seem meaningful but are in fact relatively inconsequential. When we’re talking about player experience, it’s often more important that players feel that their actions are impactful than it is for them to actually be impactful. Because regardless of outcomes, choices are a mechanism for players to express themselves. Making choices helps us mold our imagination of the characters we play, inviting roleplaying and allowing the player to participate in what their character’s values and personality might be.

In that way, the final choice surprised me. After endless debate about which path I should pursue, argued by impassioned NPCs with various motives and values, it came down to making the call. The dialogue gave me plenty of space to breathe, to think. I could back out and ask more questions, even when I’d already asked all of them. And when I selected the option I’d been planning on for the past several hours of the game, I hit one final confirmation dialogue. One final bit of resistance that asked if I was sure, if I really thought I could make that choice. A tiny last-second accusation that maybe I had it all wrong.

And…I hesitated. I backed out, clicked the other option, waiting to see what it’s final urging was, if it would rebuff me in the same way. It tried, but I realized that my mind had been changed. I clicked through. Right there at the precipice I changed my mind, after everything before it had cemented my inclination towards the other path.

Having now seen both of the main plot endings, I see that my first inclination would have led to a “better” ending. The two core endings, when considered together, express a kind of hopefulness than I didn’t quite expect. But the final provocation to reconsider actually worked; it made me doubt and made me question what I really wanted and what I really thought would forge the brightest path forward. It’s not so important that my choice mattered; what made it impactful to me is that it felt like choosing mattered, like the act of making a decision was a considered part of the storytelling in the game’s final moment.

I don’t have a fully coherent theory of what the game means with its use of the word “delusion” as a currency for advancement (and, of course, in the title), but it feels like a very intentional subversion. To believe that the world can be made truly and radically better is, to some people, delusional. But as you collect more of these glimmers of Delusion you become more capable: stronger with your blade or spells, more convincing with your words. If striving to understand the world and change it is to pursue a delusion, then maybe what the game is saying is quite simple: that a delusional intention to reshape the world can be inverted to become conviction, determination, and genuine faith.