Why I’m still stewing about Expedition 33’s ending.

A warning up front: this post is chock-full of spoilers! Read ahead at your own discretion.

As we careen into GOTY season, it’s hard to avoid hearing and talking about a game that’s dominated the industry narrative since it’s release earlier this year. Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 was a critical darling and is regarded as a triumphant inflection point in the state of modern game development. Whether or not it serves as a reasonable standard for indie achievement remains to be seen (not dissimilar from the discussions that surrounded Baldur’s Gate III), but its presence in the zeitgeist is impossible to deny.

I finished the game about a month ago. I honestly struggled to situate my expectations amid the soaring praise, but in the end it was an intriguing and unique experience. However, I found the ending to be incredibly bleak and frustratingly paternalistic; enough so, in fact, that I still haven’t quite let it go, and now I want to talk about it.

A Recap

Before I get into it, let’s get the relevant pieces on the table. There are rampant spoilers ahead, so beware. The following is a very brief summary of the story of Expedition 33 following the end of Act II and approaching its final conclusion. It’s not exhaustive and there may be minor inaccuracies, but I’m pretty sure it’s mostly right.

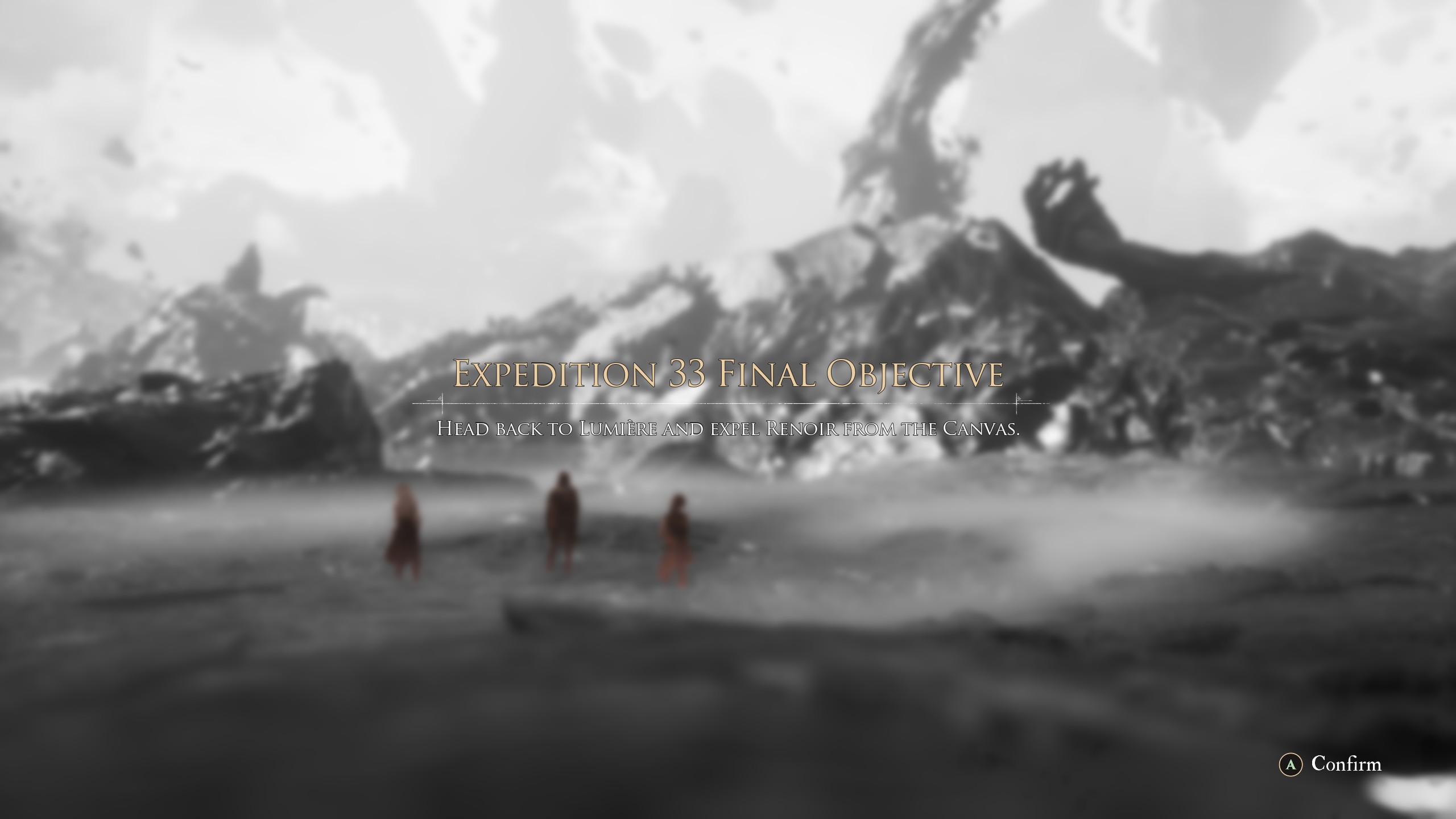

Throughout the first two acts, the adventure gradually gives way to an unfolding mystery around the Dessendre family, to whom many of the focal characters belong. After defeated the Paintress, the heroes believe they’ve saved the world from an apocalyptic force that was rapturing its population year after year. They find, however, that their victory was hollow. The survivors are unmade in much the same way as before, and we learn that Renoir, the man who’s obstructed the heroes several times and has been revealed to be Verso’s own father, is the true destructive force behind it.

It turns out, then, that the surreal world in which we’ve spent the whole game thus far is in fact a world inside a painting, a vivid fantasy realm given life by the creative powers of a different version of Verso. We learn that there is a “real” world outside of this painting. In that world, Verso has died in a terrible fire that also grievously injured Maelle’s real-world counterpart Alicia, and their parents Aline and Renoir are embroiled in a protracted struggle inside this painting. As Aline wallows in her grief and wields her power to maintain Verso’s painted world, Renoir fights to destroy her creations and return her to her senses. Eventually, Alicia (disfigured by the fire that killed Verso) enters the painting and is reborn as Maelle due to Aline’s control over the painted world. Time appears to pass differently in the painted world relative to the outside one, so she lives an entire second childhood in the painted world, surrounded by its painted folk. They are as real to her as her family outside.

After Aline’s defeat, Maelle/Alicia comes to remember her past and her life with the Dessendre family. Meanwhile, the version of Verso that’s present within the painted world struggles with the knowledge that he is only a simulacrum, an approximation invented by Aline to dull her loss. Maelle resolves to defeat her father and send him back to the real world, hoping to linger in Verso’s painted world and restore it to a peaceful equilibrium. But we’ve also been told about one more complicating factor: a lingering fragment of the real Verso’s “soul” (a notion not discussed in any other context) remains trapped within the painting, seemingly preventing him from truly passing on.

Maelle’s Fate

All throughout Expedition 33, great care is taken to center Maelle within the story while rarely putting the player into her perspective. One of the only times that we control her on her own is a brief flashback before Act III as her real-world counterpart Alicia, in a sequence that only drives home her passivity and helplessness.

After Gustave’s death, we saw the “Act II: Verso” title card and jumped seamlessly to Verso’s perspective. We learned about the Dessendres as our charted their course to the Paintress’ doorstep, all the while controlling Verso and building his relationships, seeing through his perspective despite the many secrets he still kept. After defeating the Paintress and witnessing the aftermath, we see the title card for “Act III: Maelle”. We briefly wander Lumière in her shoes and witness her decision to liberate it from Renoir’s tyrannical unmaking, and her escape from the city with Verso and Esquie.

Then, we return to camp, reunite with our friends, and… find ourselves once again playing as Verso. Maelle is the last “real” person in this painting besides the primary antagonist, and her fate is clearly the heart of the story, but we never experience the world through her unless we’re wallowing in her trauma. Later, we can play an optional sequence where she defeats and mercy-kills the tortured, silent doppelgänger of her real-world self that has haunted her throughout the game. No matter how much the story is about Maelle, it is rarely told through her perspective.

Despite this, after the final confrontation with Renoir, Expedition 33 ends with a choice. Maelle insists on staying in the painting, but Verso believes that she must leave for her own sake. The game pulls back to a dialog menu and implores the player directly: choose which character you would like to inhabit in this disagreement.

This choice presents the us with some control over how the narrative will end, but any video game with multiple endings will always invite comparison. In the wider cultural discussion, they exist in tandem and in opposition. The whole of the story includes both of the diverged endings, not either ending alone.

While the notion of multiple endings is often portrayed as responding to player choice, in some cases it can feel much more didactic. A single binary choice invokes questions: did you, as a player, come to understand the story’s thematic intentions? Can you determine which decision leads to a “good” ending and which one leads to a “bad” ending? The game may or may not label them overtly (and indeed, many so-called “bad” endings aren’t meant to be punitive), but nonetheless, the approach tends to reward players who choose the thematically appropriate ending by leaving them with more closure, more gravitas, and sometimes even a sense of moral superiority. Sure, it’s entirely up to you which ending you want; but between the two options, one perspective will be proven right and the other will be proven wrong.

Two Endings, One Message

More words are exchanged in the fight between Verso and Maelle, but the proper endings happen in the cutscenes that follow, denoted by an “Epilogue” title card. Verso’s ending is a long and somber moment depicting the Dessendre family in the outside world, standing over Verso’s grave, cathartically grieving and seeming to rediscover a semblance of unity. It suggests a hopeful future in which they can move on from this trauma, together. Alicia lingers beside the grave after the others leave, clutching a plush Esquie, and watches sadly as apparitions of her painted friends wave goodbye and dissolve away.

Meanwhile, Maelle’s ending begins with a slow zoom into a grand theater in Lumière, where we see characters from the game resurrected and happily reunited. Maelle sits among them, watching them arrive. Her expression darkens as the music drops and the lights go out. When they come back up, everything is in grayscale and an aging Verso appears on stage approaching a piano. He hesitates, a pained expression on his face. The sinister turn is punctuated by a dissonant piano sting and a cut to Maelle’s face, which is mottled with melting paint like her mother’s was, seemingly indicating her declining health as she refuses to leave the painted world behind. As an image, it mirrors the disfigurement that seems to define her existence in the waking world, reminding us that she can’t truly escape what’s happened to her.

Both endings prove Maelle wrong. In Verso’s ending, she’s a grieving child brought back to a grim reality that she has no choice but to accept. In her own ending, she’s a grieving child playing pretend in a demented dollhouse. Whatever she wanted, whatever she hoped for, she was wrong and her father was right, as was the simulation of her brother. The painted world is portrayed as a childish fantasy, but the “real” world she returns to is an equally unserious one: as far as we’re ever shown, it’s a world that ends at the steps of her family’s manor, is inhabited by four people, and is characterized by an offscreen “war” between the capital-P Painters and the capital-W Writers. It’s a world in which she is silent and her future is determined by others. That’s the world in which she belongs, according to these endings, and the game offers no further evidence of its “realness”.

The other discomfiting factor is Maelle’s disability after the fire, which leaves her unable to speak. I do not intend to suggest that her life in the real world is made unlivable by her disability or that there’s no peace to be found in the wake of her trauma. There can and should be a life for her outside the painting, and her disability should not erase her as a person. But Verso’s ending makes absolutely no moves towards depicting this notion. The whole time, I was begging someone to please get her a prosthetic eye, or to even gesture at an attempt to let her communicate without use of her voice. I’m not an expert on the disability politics at play, so I’ll try not to put my foot in my mouth, but I think it’s evident regardless that Maelle’s agency in the matter is deeply minimized by the way that she’s portrayed across these two endings. Even if you’re able to see Renoir as a loving and desperate man trying to get his family back, it does not change the fact that he calls Maelle “a living ghost” when trying to convince her to return to a world in which she can’t speak. There is no escaping the fact that Verso’s ending takes this choice away from her.

What Are You Trying to Say?

For better or worse, a sharp thematic clarity emerges from this dual-endings style of conclusion. It presents a clear dichotomy between two worldviews and forces the player to align themselves with one or the other, and in doing so, says something about both the characters themselves and their understanding of the world they inhabit. They form the two sides of the coin that is the ending’s overall thesis. The two endings of Expedition 33 suggest different outcomes, but do not imagine different possibilities.

Throughout Expedition 33’s final act, questions are raised about grief, trauma, and legacy. The final choice hinges on the fuzzy lore of the paintings themselves, and the suggestion that the Verso we know is not, and can never be, the real Verso… but that he is also somehow connected to the lingering fragment of Verso’s “soul” that prevents him from passing on peacefully. Maelle insists that her father will destroy the painting against her wishes as soon as she leaves, and that seems to be borne out by Verso’s ending. If we believe that Verso’s soul is somehow trapped in the painting, then perhaps it’s a mercy. If we believe that anyone else in the painted world is a person in any meaningful way, well… that makes things more complicated.

In the endings as presented, the metaphor is much clearer than the metaphysical implications. For Maelle to linger in the painting is to refuse to let go of someone who’s gone, and for her to leave is to take the first step towards moving on and accepting both Verso’s death and her own disability. Maelle’s desire for anything else is portrayed as selfish and deluded. Meanwhile, the only way for Verso’s “soul” to move on seems to be the destruction of his life’s work (or at the very least, his childhood drawings), which is a confusing signal about the meaning of one’s art in the context of grief and legacy.

At the end of the day, Maelle is proven to be incapable of knowing herself. She must be rescued by a parent whose affection is barely perceptible through his self-righteous rage; that’s what leaves me feeling so negatively about this pair of endings. Throughout the story we see Maelle being brave, determined, and occasionally self-destructive. But at the end of the day, she is completely reduced to someone who must be saved from herself, unable to face the truth of her disempowerment unless coerced into doing so. Her father, who spends most of the story destroying every remnant of Verso’s work, is the one who ultimately knows better, the one who’s seen the truth of things through his own past trials and now shepherds his family into the light. Never mind that the world he returns to is one he seems to preside over. Never mind that the world he returns to restores his agency and diminishes hers. Maelle, it turns out, was never a person whose eyes we should try to see through; better to make choices for her instead.

These endings are, of course, designed to evoke a response, to overwhelm with sadness and catharsis. My frustration with it comes from my own interpretation, and others may see either ending more charitably or positively. Let me know what you think, or if anything I’ve said here resonates.