Over the weekend, I attended a local convention called KublaCon Fall, an off-season supplement to KublaCon Prime (which runs in May). Silly name aside, it’s an approachable local convention that I hadn’t been to before past this weekend, and I played some new games. So without further ado, here are some (long-winded) impressions!

Our Brilliant Ruin

The first game I played was Our Brilliant Ruin by Studio Hermitage. It was an original adventure by the GM, who was running the game as a member of a demo and playtest organization that was works with the publisher. The provided characters were primarily pre-generated ones from the book itself.

The game is part of a constellation of media that form into a big IP blitz, including an ongoing audio drama and an upcoming video game. This kind of production-maxing admittedly puts me off, but since this event had open slots and seemed like a unique system, I gave it a shot.

Our Brilliant Ruin takes place in the final bastion of an apocalyptic world, where light from a distant star has brought a destructive force called Ruin that devours anything made of metal and metaphysically corrupts anyone it comes into contact with. It’s a socially-stratified setting with Gilded Age trappings and supernatural undercurrents. The book is very setting-forward, from what I could tell browsing through it, which is unsurprising given the multimedia project that it slots into.

The session felt a lot like trad games I’ve played in the past, even if the system seemed to stretch against it a bit. The amount of world-building in the book can’t really be absorbed by the scope of a convention one-shot, but I could certainly feel it etched into character sheets and capabilities. These sheets were both flavorful and economical, making it easy to understand my capabilities and archetype at a glance.

The dice system involves rolling d6s and looking for more 6s than 1s. I found it difficult to form an intuition about the dice math; as the dice pool grows, your chance of a positive outcome changes fairly subtly. Even though more dice technically improves the odds, each individual die you add is just as likely to screw you over as it is to grant or reinforce a success.

Our GM was as flexible as he could be within a prewritten-adventure style of play, but he did have to short circuit certain paths once or twice to keep us on track. The group also over-indexed on planning, with several players asking the same questions of the same NPCs and hoping to get new answers with new rolls, dragging out some of the opening scenes.

The system design seems to draw most from World of Darkness games’ narrative and mechanical blend (and indeed, one of its writers is Justin Achilli, a White Wolf veteran). A lot of the resulting dynamics hewed towards how a D&D adventure with an upstairs-downstairs twist might play out, though the scenario that the GM brought could have been a big contributor.

I found it hard to play a noblewoman character in the context of a “go to a poor rural village and hunt a monster that’s terrorizing them” adventure; the aristocrat character felt out of place doing dangerous, violent, hands-on work, even though the epicenter of the haunting was an noble family’s abandoned manor. I suspect that with the right massaging, this tension could be ameliorated or at least made more interesting, but as it was there was some friction that didn’t feel especially fun.

Overall, the game felt like it belonged deep in its own big sprawling setting in a way that couldn’t shine in a convention setting with players who had no prior experience. I don’t think it suited my sensibilities, but the PDF is free and it seems to be thoughtfully crafted, so it’s worth checking out if the pitch sounds intriguing.

Royal Blood 2e

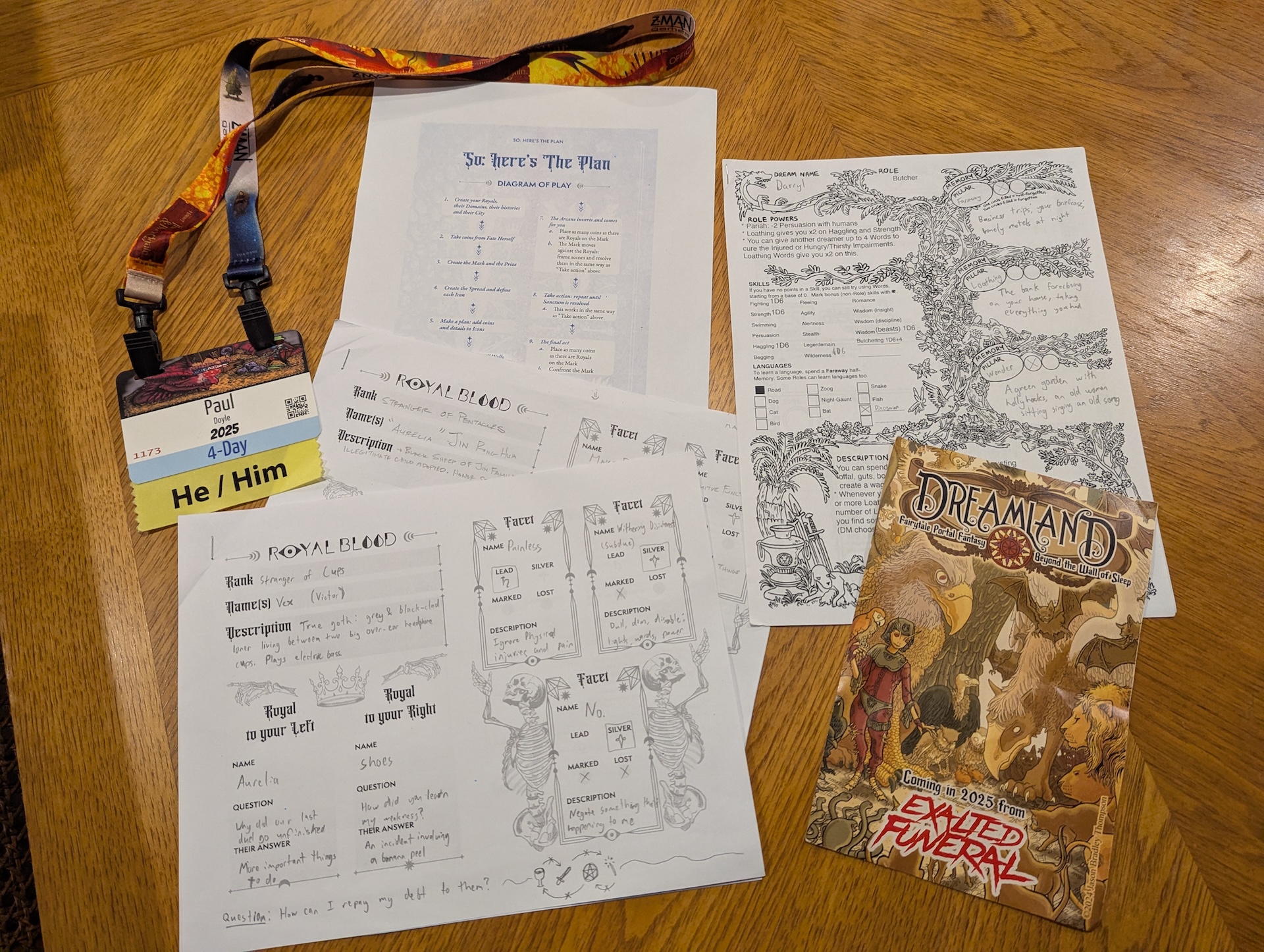

Royal Blood is a game by Rowan, Rook, and Decard that funded a lush redesign and rerelease on Kickstarter late last year. It was the first I’d heard about it, but I’m familiar with a chunk of Rowan, Rook, and Decard’s output (as you may have seen in other posts on Eat the Reich, Heart: The City Beneath, etc.).

The game involves establishing characters and setting around the core concept of ambitious magic-users in a modern-day city who band together to dramatically dethrone a powerful magic wielder called the Arcane. The game is fueled heavily by tarot as both an aesthetic cornerstone and an oracle for storytelling.

A good chunk of our session was spent during setup; a nontrivial sequence of steps guides the group through building characters, detailing the world, and establishing the obstacles in front of the protagonists. This is certainly not a bad thing (setup is also play!), but I could feel it straining the time management of our four hour play session. Ultimately, we went a half hour past our allotted end time.

After setup, the remainder of the game involves several phases built around a simple token economy and a tarot card drawing mechanic, in which players can stake more resources to get more card options to choose from for their outcome. Different cards produce different results, so widening the pool of options feels quite meaningful, a lot like rolling with advantage.

The writing of the game is maximalist and indulgent, which is (along with the sheer density of drug references) very recognizably Grant Howitt’s style. It works well most of the time, but occasionally overstays its welcome and makes scanning and remembering details a struggle. For example, each character has “Facets” that they use to contend with challenges and must risk losing in order to progress; each one has an entire paragraph of flowery description, but lacks a single-sentence summary to remind you what it actually is or does.

The tarot artwork by Silvia De Stefanis is lovely; there’s no shortage of gorgeous tarot decks floating around in the Kickstarter ether, but these cards still hold their own and complement the game nicely. Since the Kickstarter hasn’t shipped, our convention GM got a deck printed on glossy card stock and they served us well during the game.

On that note, I also appreciated that the GM constrained our setting with a conceit of his own (high school goths overthrowing the queen bee of the school). It led to exaggerated characterization that suited to the game well and was easy to play into for a convention setting.

Overall, Royal Blood’s top-level procedure felt like a little bit too much, but the bones of the game and its resolution system were punchy and the tarot interpretation was a well-integrated element. Even with a GM guiding the story, these interpretive moments felt very collaborative. I also managed to convince my partner to join the game, which made it all the more fun. I could see myself revisiting Royal Blood to run it for friends at some point.

Blood on the Clocktower — Trouble Brewing and Bad Moon Rising

I first heard about Blood on the Clocktower at Big Bad Con, when I was making small talk with other volunteers in the break room. It’s a social deduction game, akin to Mafia or Secret Hitler, in which each player is given a hidden role and a team alignment and then tasked with eliminating fellow players until their team emerges victorious.

Designed by Steven Medway, Blood on the Clocktower feels like, as far as I can tell, the mother of all social deduction games. It’s built modularly on a foundation of simple rules and then thrown into elaborate strategic chaos via the introduction of dozens of unique character roles, each with a unique ability that lets them contribute to their team in a distinct way.

The structure of a Blood on the Clocktower game takes place across several days and nights. During the day, players converse and share suspicions and theories, then nominate players to execute and cast votes. During the night, players take turns triggering their hidden abilities while the rest of the group keeps their eyes closed. Layered on top of this basic format are “scripts”, curated sets of roles that produce certain strategic and social dynamics alongside a set of instructions to follow in order to run the game and proceed through each night.

This brings me to the most distinctive aspect of Blood on the Clocktower: there is one person who has no role at all in the game’s fiction. Instead, they function as the “Storyteller”, a neutral facilitator who carries out the procedural steps: they tell players when to open and close their eyes, call for nominations and count votes, manage individual player abilities during the night, and announce the results of those actions. All of this is performed in a prescribed order to ensure that everything fits into place neatly, often leaving space for mechanical edge cases but ensuring that they’re clever and intentional.

Beyond the precision and simplicity of the core rules, the Storyteller manages every piece of procedure and information visibility, making the whole experience feel smooth and curated. Using these tools, an effective Storyteller may also adjust balance and spotlight certain interactions. They can make choices about which roles from the pool are included in a given game. They can determine which players are affected by certain abilities and can make on-the-fly balancing decisions (all within the stated rules) that keep the drama high and ensure that victory is won cleverly or narrowly.

In both of the games I played, each with a different script (Trouble Brewing and Bad Moon Rising), each of which had more than 20 unique roles, I landed in the role of a Minion, a second-in-command to the lead antagonist Demon. In both games, I was soon pulled aside by the Demon (a more experienced player, luckily) and given advice on how precisely I should lie to other players about my role and its abilities. There was a palpable play culture among the cohort of seasoned players I interacted with: unstated habits and strategies, references to other scripts or past play experiences, and so forth. All of this was a bit alienating at first blush, but it was meaningfully tempered by the presence of a neutral Storyteller who could answer questions.

Playing an evil character in both games was exhausting, and not just because of the complexity. I think it’s fair to say that I have an aversion to social deduction games in general. I find tactical deceit to be stressful and viscerally unpleasant; whenever I draw an evil role, I feel my stomach knot up and my heart rate elevate. I can imagine the appeal: there’s obviously a thrill to getting away with ingenious deceptions, to pulling one over on your friends with poisoned logic or careful acting. It truly isn’t fun for me, but I can understand the sort of competitive impulse that it appeals to. I don’t mean to say I didn’t have fun; I just experienced an inordinate amount of stress along the way.

But I have a million more thoughts about the Storyteller role and the ways it intersects with GMing in traditional TTRPGs and wargames. This post is long enough as it is, but suffice it to say that the mere introduction of a neutral facilitator creates so many possibilities. They can answer rules questions mid-game without giving things away, they can apply “randomness” to abilities (e.g. one-out-of-two chosen targets gets this effect), and they allow role abilities that involve believing your role is something that it isn’t; all of which Blood on the Clocktower was doing in the mere two games of it I played*.* The inclusion of the Storyteller truly explodes the design space, and while the game itself is hard for me to stomach, I’m profoundly intrigued by the notion of filling the Storyteller role. In a sense, even with its truly overwhelming complexity, Blood on the Clocktower seems to be offering an alternative way to participate—even for forever-GM social deduction haters like me.

**

The last proper scheduled game I played was a late Saturday night session of Dreamland by Jason Bradley Thompson, run by the game’s very own writer, designer, and illustrator.

Dreamland draws heavily on the stylistic trappings (and also the literal words) of Lord Dunsany’s writing, among many other inspirations, and functions by using an intriguing wordplay system to augment a more traditional “skill check”-oriented foundation. Players portray characters who inhabit a dream world and have only a few specific memories of their waking lives. During the game, they endeavor to solve problems in the dream while periodically intersecting with their waking lives, either by waking up entirely or experiencing events that blur the boundaries between the dreaming and waking worlds.

Whenever players need to take difficult actions, they attempt to meet a target number and may roll skills or start from zero to do so. Either way, players can increase results by interacting with a unique wordplay engine that asks them to poetically describe actions and outcomes, either as in-character monologue or out-of-character narration, using a pool of provided word cards laid out in a grid. The resulting storytelling leaves room for flowery and dramatic descriptions, as well as a degree of overt dream logic (which occasionally came into play to help us circumvent tricky problems).

Intentionally or not, wide vocabularies and articulate improvisation are socially (if not mechanically) rewarded by Dreamland's word system. As is often the case, you can feel when mechanical incentives take precedence over roleplaying or writerly impulses. But throughout our session, Jason was admirably reassuring and encouraging about the varyingly eloquent dictations that got us out of trouble. Despite the awkward social challenge of building narration while also attempting to use keywords, I found it to be a genuinely endearing system to engage with: it often produced little swerves or flavorful details to the fiction that would not have emerged from dice alone, and it did so in a structured way that a GM could somewhat anticipate just by keeping an eye on the word pool. It also provided a lot of agency to players wanting to avoid direct failures in exchange for risking alternative consequences. I had relatively bad luck that evening, but I always felt like I had a good degree of control over what I risked and when. That kind of flexibility can be quite hard to produce.

Overall, I sometimes found the waking/dreaming lives concept to be a bit of a distraction from the core (dream world) fiction of the scenario, but I could see how it would function better over multiple sessions. Dreamland has an unusual system that surprised me in a lot of ways, and I’m looking forward to seeing it release fully. I couldn’t say if I’ll run it in the future, but I’m certainly not counting it out.

Playtesting Jajanken Duel

Before I left for the day on Sunday, I got a chance to playtest a slightly revised version of the Shonen dueling game I wrote for day 5 of promptober, with the help of a local friend who was at the convention. The playtest revealed a few points of logistical friction as well as some rules text that needed more clarity, but I was surprised to find a lot of intrigue and tension in the core structure of the game.

Jajanken Duel (as I’m temporarily calling it, Hunter x Hunter inspiration on its sleeve) is a rock-paper-scissors powered card game about anime characters fighting it out, using cool powers and trying to outsmart and one-up each other. But the story my friend and I told involved a setup that quickly led to both of us being reluctant to continue the fight, even though its stakes were still at play. By the end of the game, neither one of us was explicitly trying to win rounds, especially not with offense; we were instead trying to guide the story towards a cathartic ending for our characters, rolling with the punches along the way as the narrative squirmed in our grasp.

The game played from start to finish in about 45 minutes, which is great news for future playtesting. The fact that we were able to reach such dramatic intensity so quickly was an equally encouraging surprise, and the tension between narrative intent and the mental game of rock-paper-scissors became both disorienting and fruitful. It’ll need a lot of tempering to feel smooth, but the potency of the effect is proof to me that there’s something here to build off of.

I tend to feel extremely vulnerable when playtesting games with friends, especially when introducing folks to my work for the first time, but I always come away energized and touched by their kind, thoughtful feedback. It was a lovely note to end the convention on, and a reminder that in addition to scheduled events, conventions like this provide a space that erodes the burden of planning and leaves pockets of downtime to casually explore games with friends.

Conclusion

And that’s a wrap for KublaCon Fall. I even managed to not buy anything from its humble selection of merchandise vendors! Please clap!

In general, KublaCon had fewer scheduled events that captured my interest than Big Bad Con (which featured more story games) or Gen Con (which was simply gigantic). But the laid-back experience of a local convention helped me prioritize spending time with local friends and pacing myself with games and time spent at the con. I’m starting to find healthier rhythms with these kinds of events that leave me less drained; hopefully this means many more conventions in the future.