In the last month or so, I had the chance to run a 4-session game of Eat the Reich, the recent ink-drenched, ENNIE-winning, nazi-slaughtering vampire adventure from Grant Howitt, with art by Will Kirkby, published by Rowan, Rook & Decard. It’s intended to be played as a high-octane no-prep action movie 3-shot (ish) in which a squad of vampire commandos treks through an alternate-history nazi-occupied Paris to put a bloody stop to Hitler’s conquest.

To accomplish its action-blockbuster concept, Eat the Reich stacks its design with mechanisms that produce and maintain momentum, angling for a bombastic ultra-violent romp that barrels headlong towards a ridiculous and spectacular conclusion. These mechanisms are both indulgent and clever, locking the game into a tight structure akin to turn-based combat encounters in traditional TTRPGs without quite eroding the narrative-driven sensibilities.

Despite this, I encountered a number of challenges running the game, edge cases that threatened or undermined the crucial sense of momentum and left me trying to plug holes. As I’ve found with several of Grant Howitt’s games, the book implies a lighter lift for the GM than my own experience at the table bears out. With Eat the Reich in particular, the structure and rhythm at the game’s core is refreshingly straightforward. But across several sessions, it became a more concentrated effort to keep intensity high and creativity rewarding.

My overall experience with Eat the Reich was pretty positive, and my players enjoyed the change of pace and the over-the-top premise. But it left me thinking a lot about what makes turn-driven encounters tick and why the game’s myriad ways of maintaining inertia still created odd pitfalls at our table.

All Gas, No Brakes

Eat the Reich uses of a level of structure that traditional TTRPGs often apply specifically to combat encounters. To some degree, nearly all of Eat the Reich could be describe as one of three things: a combat encounter, a quiet start to a soon-to-be-combat encounter, or an action or intrigue set piece with the intensity of — yeah, a combat encounter.

This is a little reductive, as there are generally non-combat objectives that are centered, but I think the comparison still fits. Players of D&D or other trad games in its lineage can attest to a problem that frequently occurs with combat: the pace of actual events occurring in the game slows down so much that the momentum of play stalls and the game becomes a rather tedious math exercise. Even players who do their best to stay engaged may lose focus when it’s not their turn to act, especially when playing virtually. While Eat the Reich gains clarity and simplicity by slotting in a classic turn structure, it also risks producing the kinds of problems endemic to 3 or 4 sessions of straight combat encounters.

Howitt clearly knows that this risk is present, and the system is designed to (forgive the pun) combat that kind of repetitiveness. It’s driven by the Havoc Engine, a resolution system initially conceived for Howitt’s Havoc Brigade (a trope-inverting fantasy game about chaotic orcs). In its Eat the Reich incarnation, it’s driven by pre-generated player characters with arsenals of dramatic vampiric weapons and abilities. During a turn, players choose an action (most often BRAWL or SHOOT, but also including things like SEARCH and TERRIFY), start with their stat in that action, add bonuses for weapons and abilities they’re using, and roll a big pool of D6s. Each 4 and 5 is a success; each 6 is a crit (which can mostly be used as two successes instead of one). Each success is allocated towards dealing damage to opposing forces (called Threats), completing the Objective for that area, stockpiling Blood (a resource for healing injuries and activating abilities), and deflecting damage generated by the GM’s dice pool.

There’s a mischievous joy to cobbling together elaborate actions, trying include as many boons as possible, and it allows a fun degree of variety between any two turns based on the situation, focal objective, context of the scene, and the toolkit of the acting character.

Beyond the expressivity of individual turns, though, is a stack of broader systems that keep the action surging forward. Players only stay at a given location until the Objective (with a given number of points) is cleared. Any Threats that players eliminate will “respawn” by way of reinforcements arriving at the end of the round, a weakening but never-ending assault. Players can freely share Blood, the resource that drives their healing and abilities, as long as their characters are roughly nearby one another. Once per session, each player can re-roll a poor result by invoking a Flashback: they narrate some history between their character and another, and then roll again with 2 extra dice. Players take injuries if they fail to (or choose not to) block damage, but they won’t see any consequences from them until they’ve taken several. And while Equipment and Loot all have limited uses, the final use typically grants an extra die — a little extra incentive to use that final charge instead of hanging onto it.

Overall, the pressures add up for players to build big, wacky dice pools, focus on objectives rather than killing every enemy, and accept occasional injuries rather than fixate on blocking damage. All of these forces keep players moving through each location without lingering too long. Right?

Brakes, After All

At the turn level, it quickly became apparent that a fight can stagnate whenever the Threats facing the party roll well against them. Players may feel that they need to spend all or most of their successes simply blocking incoming damage to stay on their feet, and their turn may come and go without progressing Objectives or whittling down Threats. Once my players got their footing, they started to push harder to make their own dice pools bigger to counteract these stalemate, but a particularly dangerous set of threats always risked producing a lot of nothing-happens turns unless players were more willing to take injuries.

And while there was certainly plenty of creativity involved in crafting an interesting action for a given turn, our table found some actions (and by extension, some characters) felt limited by their options when they were not in situations that overtly invited those actions. Eat the Reich’s 7 action ratings can be easily divided into two categories: the obviously useful ones (BRAWL, SHOOT), the occasionally useful ones (SNEAK, TERRIFY), and the rarely-used leftovers (CON, FIX, and SEARCH). Beyond being less applicable to the most common situations, these last three also needed to stretch a bit farther to justify applying them to certain objectives or threats. In the end, it became clear that some characters had very easy ways to combine their best stats with most of their equipment and abilities, and some simply didn’t.

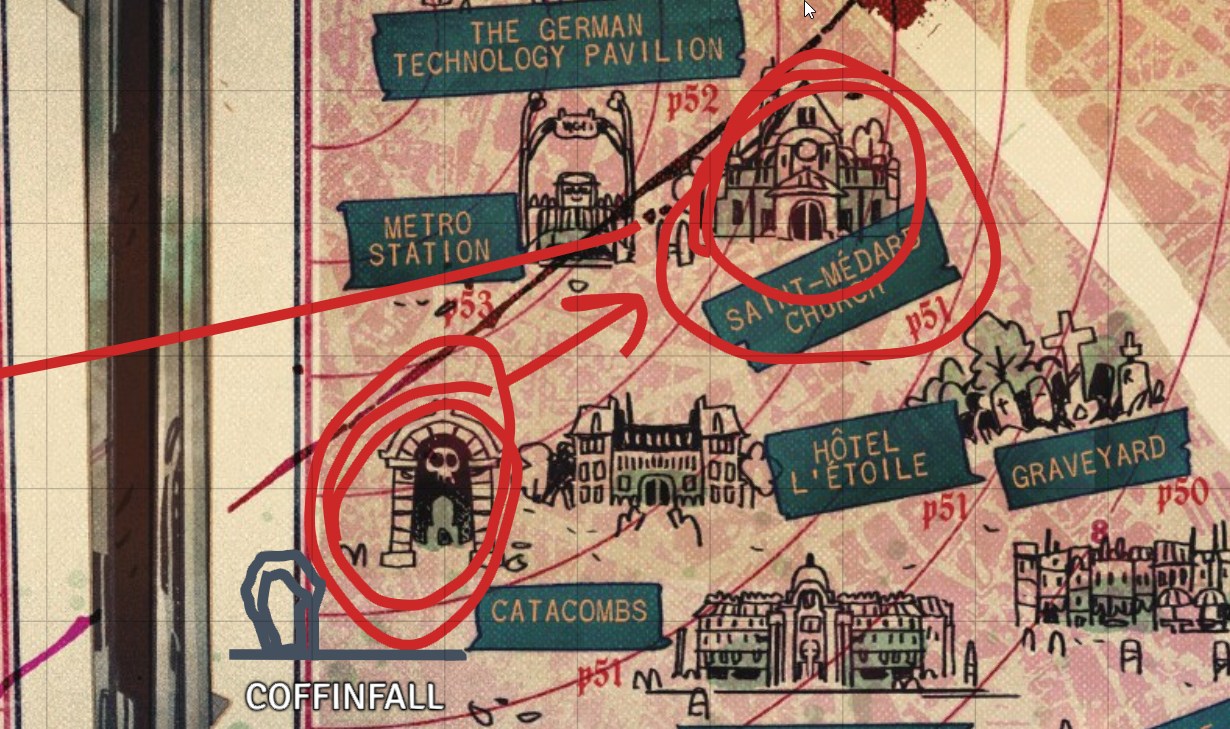

Beyond individual turns, Eat the Reich has similar structural edge cases. Each location on the map of Paris provides a brief description of what’s going on there, the kinds of Threats and loot to be found, and an Objective to complete before moving on. A few locations contain Ubermenschen, powerful supernatural nazi experiments that pose especially dire threats to our squad of vampire anitheroes (and the world). Defeating one of these area bosses allows everyone to choose an Advance from a short but tantalizing list of powerful additional abilities. This is the only progression that the game offers, so my players were obviously drawn to seek one out.

Naturally, boss enemies are one-of-a-kind, so they’re explicitly exempt from the rules for reinforcements. That means that anywhere that an Ubermenschen can be found, players may be implicitly incentivized to focus all their energy on defeating that threat (and claiming their hard-won advance), which leaves the actual objective and any straggling minor Threats feeling extremely perfunctory once the boss is defeated.

Moreover, the big picture elements of the setting benefit from a context and foreshadowing, and in fact the Ubermenschen each suggest imagery that might foreshadow their appearance. But the majority of play was so focused on each location’s scenario that it was difficult to keep this in mind, and it was unclear how to guide or constrain the party’s decisions of where to visit next.

If You Don’t Like it…

In the (relatively brief) “Running the Game” section, there’s a note directly encouraging GMs to abandon or change any rules that aren’t serving their table or making the game fun. If I’m encountering issues with the rules, why not change them, right? Well, I did! A little! I don’t personally find it easy to change rules on the fly for a game this short, but I did what I could to adapt it to my table. In a few cases, I twisted and bent the rules to generate more tension, provide a bit of relief, or reward ambitious play. Any deeper changes felt like they might cheapen the creativity and resource management that players had done up to that point.

As we were feeling out the system, enemies with high attack ratings felt like brick walls. I started splitting their attention. For example, this Sniper Team can only focus on 3 out of 5 of you, and you all get to decide based on your action if you’re drawing their attention or doing something else while your teammates keep them busy. This turned out to be a nice way for players to strategize as a team, either volunteering to distract or taking opportunities to to push objectives with less opposition. As we progressed further and players started to push their characters harder, I dropped that modification. It felt like a good set of training wheels to add and remove as needed, but I might have better telegraphed it with precise language (perhaps a Sniper Team that split its attention could later have been swapped with an Elite Sniper Team that had no such restriction).

Later on, we encountered our first Ubermenschen. The fight felt insurmountable at first, but after a tough battle and some effective use of abilities, the players were victorious. Once it was over, they were left with a somewhat plodding push through an Objective that was (reasonably) untouched by the time the fight ended; I wound up introducing more minor Threats just to keep some pressure on, but it ultimately dragged out the escape, without actually making it any more harrowing. In retrospect, I ought to have taken a particular bit of advice in the “Mission Structure” section: “If there’s nothing particularly interesting happening in a location, hand-wave past it and progress onto the next exciting thing that happens.” But it was tough to justify just skipping the Objective when it seemed to be about escaping the current location.

Towards the end, several players had been taking on a lot of injuries, but didn’t want to slow things down by “farming” Blood, as it were, before pushing through Objectives. To balance this back out, I let players heal one injury each time they moved between locations, as their vampires had a moment to catch their breath before the next big encounter.

And finally, at the end, after we skipped past a couple of locations in order to wrap up our final session, the players dispatched a surprisingly underwhelming “final boss” Ubermenschen. Trying to reignite a bit of drama, I pulled out a stronger enemy that they hadn’t encountered, had it absorb one of the abilities of the defeated Ubermenschen, and gave the players one last challenge in between them and Hitler-murdering satisfaction. This didn’t give them too much trouble, but it did help make the ending more bombastic, and I was happy with the adjustment.

Hacking at the Table

I don’t typically like to hack games apart at the table to adapt them to my group or my concept. I like to hold rules close in hand and try to experience and engage with what those rules produce. My home group is curious and flexible, and they’ve let me bring a lot of different games to the table over the years. When we play something new, we tend to want to play that thing, not massage it into whatever fits our rhythm. Rules are written in particular ways for particular reasons, and sometimes adhering to them more than we intuitively might is a good way to understand their intentions and strengths. Giving a game’s rules attention, patience, and grace can encourage different kinds of play than my players and I might typically gravitate towards, and it’s one of the reasons we like to try out different games.

I really like a lot of things about Eat the Reich, especially its size and scope. It’s a fairly lean 70-page book designed for short, explosive campaigns. It occupies a rare niche between small games that I can read in a half hour and play in a session, and hulking campaign games designed for hours of perusing and hundreds of hours of play. And even in its brevity, Eat the Reich manages to spill a lot of ink towards helping players and GMs thoughtfully handle its subject matter. The advice in this book on how to portray nazis, vampires, accents, violence, and the possibility of harm to innocents is all remarkably strong, measured, flexible, and specific.

In a game so dense and so brief, there’s a lot of pressure to make the right changes for your table if you choose to fiddle with the design on the fly. In the end, as with all games, running them makes you better at running them. I have ideas of which alterations I’d keep and which I’d drop for future play, and I’ll now remember important details that are easy to forget or overlook. If it's your first time running Eat the Reich, though, be ready to get a little bit creative to help your table stay entertained and engaged.