This is the second part of my 2-part blog series on Spire and Heart (Rowan, Rook & Decard), and the ways that failure and consequences intertwine with the stories we tell at the table. Check out part 1 here.

Last week, I discussed how Spire: The City Must Fall initially left me a little cold, wrong-footed by how my expectations conflicted with the way the dice hit the table. Meanwhile, the relative lack of friction didn’t cause my players much consternation at all; they were simply progressing through an adventure.

For me, the pursuit of flavorful failures and meaningful consequences is a huge part of the joy I find in tabletop RPGs, whether I’m running them or playing them. I like to see characters struggle as much as I like to see them triumph. I like to know what happens when plans go awry, when villains gain ground, when prices are paid and stakes are raised. In many popular games and play cultures, failure often manifests as nothing more than "the thing you want didn't happen"; and I feel like that's a disservice to the storytelling potential of dice.

I’ve not returned to Spire since my initial brush with it, but I’ve had an enduring curiosity about its followup, Heart: The City Beneath (also written by Grant Howitt & Christopher Taylor). This year, I pitched another group on Heart and we're now well underway. Heart is in many ways a rare TTRPG sequel (as pointed out by E.R.F. Jordan on BlueSky): it iterates meaningfully on system and setting, and it draws focus away from certain aspects of the world of Spire and more tightly onto others.

From Spire to Heart

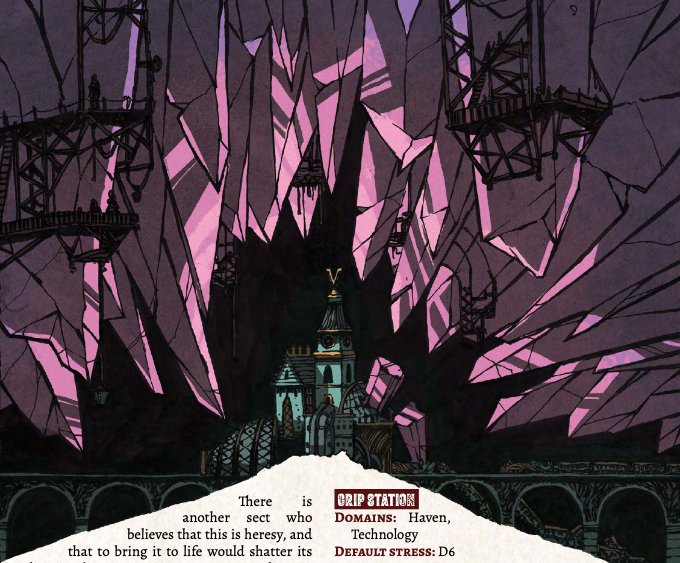

Heart veers away from revolution, instead establishing itself as a horror-fantasy twist on the already-fantastical and already-horrifying world of Spire. To do this, Heart takes players deep beneath the base of the titular Spire into a cursed subterranean land called The Heart. The Heart is named for the unfathomable anomaly at its center that twists and sunders reality around it, spilling forth grotesque beasts, bizarre landscapes, and incredible secrets. Its draws inspiration from Roadside Picnic, Annihilation, Bloodborne, and more. The world of Heart is harsh and lethal, but it’s also deeply alien, in ways that can be just as existentially beautiful as they are terrifying.

This thematic shift turns the protagonists from stoic freedom fighters into a morally broad collection of explorers, survivors, peace-keepers, and truth-seekers. Heart’s main characters are “delvers”, people compelled (either intrinsically or extrinsically) to seek deeper levels of the Heart’s strangeness and uncover its greatest mysteries. Many kinds of folk can be found in the Heart, and survival and subsistence is so all-consuming that the racial and cultural tensions of the world above are (perhaps a bit awkwardly) pushed into the background.

Systemically, Heart takes loose inspiration from hexcrawls, a style of crunchy map exploration characterized by traversing tile to tile and finding monsters and secrets as you work towards broader objectives. Heart asks players to descend into strange landmarks in search of valuable resources or knowledge, leaning more on the grim fantasy setting of Spire than its topside political turmoil. To sell the treacherousness of the Heart, it adds a crucial twist to Spire’s mechanic for added difficulty: while Spire reduces the number of dice in the pool you roll with (e.g. 3d10 → 2d10*)*, Heart leaves the pool untouched until after rolling, and then cruelly culls the highest value from the results (e.g. “10, 6, 2” → “6, 2”; this makes a meaningful difference).

Heart’s Stress system works similarly to Spire’s, but its locations and adversaries classify the amount of stress that they might incur more directly. In Heart, any degree of additional difficulty will steer players sharply towards Stress and Fallout. But there’s a good reason for this: Fallout is a key part of the narrative rhythm of the story. Spire’s three-ish pages of Fallout options cover straightforward events like bleeding wounds, favors owed, a bounty on your head. Heart, meanwhile, dedicates a whopping ten pages to describing all the fucked up things that can happen to player characters. Fallout can establish plot hooks or intrigue, and many of the options can be “upgraded” into more serious problems. Some are just unapologetically upsetting, like vomiting up a handful of parasites, suddenly losing a light source in the dark, or having “reconfigured physiology” (I’ll let you just imagine that one).

At the Table

This sounds like good fun and all, but it did take my group some time to acclimate; even Heart’s gentlest areas have the capacity to be harsh, so when difficult rolls appeared, Stress started to accumulate and Fallout loomed. The players were making progress, but felt a little caught off guard; they questioned whether the stress I was inflicting was too much for the early game. I assured them that, per Heart’s advice, the players were in control of their ultimate fate; the consequences that I was holding over their heads could slow them down and even change them, but only the players could decide when their doom arrived.

After a while, Stress began to turn to Fallout and the group started to see what the game actually looks like. What at first seemed overly harsh took on a different color under the light of Heart’s twisted setting and its delightful variations on Fallout. While both games’ lists of Fallouts provide a mixture of plain old debuffs and entirely new problems, Heart’s are more geared towards advancing stories and making the world feel more treacherous and interesting. Some Fallouts, if left unattended, could easily entwine with the party’s overall pursuits or become central to their story. Others become little whispers of unsettling detail, causing very little immediate trouble but shifting a character’s relationship to events as they’re unfolding.

Meanwhile, presenting Fallout via a Great Big Menu of Options is a potent way to simplify GM responsibilities (even if it can result in a bit of a pause to scan the options). Not only that, but the list of options is an object over which to negotiate. Players are encouraged to work with the GM to determine which Fallout they ultimately take, giving them a reason to peruse the list themselves and imagine the possible ways their story could shift. As my group began to learn the rhythm of these exchanges, players were able to meet Fallout with a rueful grin rather than an exasperated groan.

This is one of the things that makes Heart so interesting to me as a GM. It’s a structure built upon permission and feedback, where the game’s rules are just sturdy enough to give me clear guidance and a reasonable alibi when assigning consequences, but negotiable enough that the players still have tools to adjust or argue for themselves. It’s a tidy little mirror of Heart’s Beat system, which allows players to signal to the GM which mechanical and plot elements they want to engage with, and then earn advancements when they pursue those elements. When prepping locations, NPCs, adversaries, and imagery, I look to the players’ chosen Beats. But once the board is set, the tango of difficulty ratings, Stress, and Fallout do a lot of work to make obstacles feel daunting and failure feel dramatic and meaningful — without being nearly as punitive as sheer lethality.

Story Game Structure

In story games, there will always be a critical space between where the dice fall and the narrative that GMs and players unravel out of those dice rolls. Many of the games I’ve run embrace this open-ended approach, providing generic maneuvers that help the GM tell a good overarching story. Negative consequences of rolls should “fail forward”, emphasizing the stakes of the scenario, provide intrigue or novelty, and leaving players with ingredients they can turn into dramatic comebacks, clever solutions, or compelling reasons to shift their focus.

While there are certainly gaps in Heart’s GM materials (and Spire’s too, for that matter), the ridiculous menu of alarmingly specific and nasty things that might befall the players makes for a potent tool. The game encourages GMs to invent their own Fallout if none of them fit, but the options provided will reinforce themes and cover a wide range of scenarios. Many of them also leave space to further elaborate.

Running story games can be challenging because they encourage minimal planning and discourage prewritten story structure, but they often still provide some kind of shape to fit it all into. If the goal is to tell (and be surprised by) the story as you go, you don’t want predetermined events or outcomes, but you do want ingredients on hand and a loose idea of what you’re going to do with them.

The other games I’ve run in this lineage build narrative within broad templates or rhythms: Masks: A New Generation uses “Arcs” help build and pay off drama, Apocalypse Keys has “Mysteries” with a “Complexity” score to guide pacing, and Blades in the Dark cycles between heists, downtime, and free-form investigation. Heart uses a lighter touch with overall structure and instead leans on flavorful character abilities, location and enemy descriptions, and consequences that can pitch players into interesting plots and spiraling problems.

I’ve not yet finished the Heart campaign I’m running, so I may yet have more to conclude. But for now, Heart’s amorphous and pulsating world is a fairly successful demonstration of how story can be shaped by both the PCs’ strange abilities and the world’s horrifying reactions when they risk too much or reach too deep. If your players really hate failing rolls, they might not have much fun. But if your group is willing to take Heart’s blood-slick hand and let its lurid writing guide them, it might just take them somewhere more exciting and memorable than they expected.